![]()

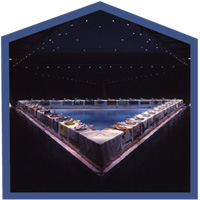

Welcome to The Dinner Party K-12 Curriculum website. I thought it might be important to discuss why I have devoted so much time in the last few years to working on this project. In 2005, my husband, photographer Donald Woodman, and I were invited to be the first Chancellor’s Artists in Residence at Vanderbilt University. By this time, plans were already underway for the permanent housing of The Dinner Party. I set this goal for myself even before the piece was finished in 1979 and began its worldwide journey that eventually brought it to an audience of more than one million viewers. Over the course of the years, Through the Flower received many testaments by K-12 teachers all over the world who had used The Dinner Party in their classrooms. Although I found these tributes charming, I must admit that I did not pay a lot of attention to them.

Welcome to The Dinner Party K-12 Curriculum website. I thought it might be important to discuss why I have devoted so much time in the last few years to working on this project. In 2005, my husband, photographer Donald Woodman, and I were invited to be the first Chancellor’s Artists in Residence at Vanderbilt University. By this time, plans were already underway for the permanent housing of The Dinner Party. I set this goal for myself even before the piece was finished in 1979 and began its worldwide journey that eventually brought it to an audience of more than one million viewers. Over the course of the years, Through the Flower received many testaments by K-12 teachers all over the world who had used The Dinner Party in their classrooms. Although I found these tributes charming, I must admit that I did not pay a lot of attention to them.

While we were at Vanderbilt, my attitude abruptly changed. I received a copy of an upcoming article in a popular K-12 art education magazine describing a class project that was supposedly based on The Dinner Party. Students had made autobiographical plates. Although I knew the teacher had not intended to offend, this interpretation of The Dinner Party deeply disturbed me. While there is nothing wrong with doing autobiographies on plates, it is a mistake to claim that such a project has anything to do with The Dinner Party, which is about women’s achievements in history.

Moreover, another of The Dinner Party‘s intentions is to help viewers think beyond the personal, especially girls and women who often drown in the many personal demands that are still placed on females in societies around the globe. Thus, a project involving autobiographies on plates defeats the very purpose of The Dinner Party. In addition to teaching a broad and diverse audience about the achievements of women in Western civilization, The Dinner Party aims to help both women and men better understand women’s experiences through the lens of history, something that is unavailable to most of us because women’s history is still taught in such a spotty and incoherent manner.

When I read the art education magazine article, I began to think about offering some guidelines for K-12 teachers who were interested in using The Dinner Party in their classrooms. Just as I consulted art and art history books along with women’s histories, biographies, autobiographies, and literature while making The Dinner Party, so can the work be used as a stepping stone into many fields of study. Being at Vanderbilt while I was pondering the idea of a new curriculum was fortuitous because it allowed me access to Constance Bumgarner Gee, who has been my guide into the field of art education.

The field and practice of K-12 art education was looked down upon when I was in college at UCLA in the 1960s, and often still is by both university art instructors and the professional art world. As a result, I knew very little about the field and absolutely nothing of the changes that have taken place during the last few decades. Constance introduced me to some of the recent literature, notably Marilyn Stewart and Sydney Walker’s book, Rethinking Curriculum in Art (2005) and Gender Matters in Art Education by Martin Rosenberg and Frances Thurber (2007). To say that I was astounded by these books would be a profound understatement.

In 1999, I had returned to teaching after a twenty-five year absence. Between 1999 and our time at Vanderbilt, I (then my husband Donald and I) conducted residencies at six universities in various parts of the country. One reason I re-entered academia was that I was interested to see what had happened to university studio-art during the time I was away. As some readers may know, in the early 1970s I pioneered a unique content-based pedagogy that was originally aimed at helping young women become professional artists without having to deny or suppress any evidence of their gender, which had been required of me when I was in college.

With Donald, I was able to apply my pedagogical methods to male as well as female students, which showed me that my techniques could be equally effective, but only if we insisted on the circle-based pedagogy that has sometimes been confused with 1970s consciousness raising but is in fact, quite different. Happily, when I returned to teaching, I discovered that there had been many significant changes: For instance, many more women and people of color had become part of art school faculties and there was greater diversity in exhibitions as well.

The most potent aspect of my methodology proved to be its insistence that every voice is important, a practice that unfortunately is in direct contrast to what goes on in most university studio-art programs where students (without regard for their personal experiences, interests, or inclinations) are exposed to the latest, hottest trends in art and expected to fit themselves into a system that eats up and disposes of young artists almost as quickly as animal innards in the brutal system of factory farming. Additionally, many university studio-art programs have continued to resist the integration of feminism and feminist theory into the curriculum. That resistance has resulted in generations of young women learning almost nothing about their female predecessors.

Art schools continue to promulgate a type of education that dates back to the Bauhaus. This approach to the visual arts consistently privileges form and material over content and, in my opinion, is inherently biased against women. Although it may be a generalization to state that women are inclined to approach art from a content base, I have found it to be an accurate one throughout my many decades of working with female students and artists. This lack of focus on content in university studio art education has resulted in increasingly vapid art production in the contemporary art world.

Given my experience and thinking about art education, one might understand why I was so surprised to discover that it was in K-12 art curriculum that a new teaching approach had evolved, an approach emphasizing content, diversity, and gender sensitivity. My abiding goal for The Dinner Party was to educate future generations about women’s rich heritage and their important contributions to Western civilization. The permanent housing of The Dinner Party was a significant step in achieving this aim. Another stride forward was the opportunity to develop a cohesive K-12 curriculum based on The Dinner Party, a means by which to bring knowledge of women’s history to countless generations of students. It is my abiding hope there will be many art teachers who will help accomplish this important goal.

Although there are many ways of approaching The Dinner Party, it is important to note that The Dinner Party is built on a solid foundation of research into history, art history, feminism, and the obstacles women faced (and continue to face) as they struggled to participate fully in the societies in which they lived. The Curriculum is structured in a sequence that is intended to help students gradually develop a consciousness about gender along with a deep understanding of women’s history, women’s art, and women’s achievements. The Curriculum consists of a series of downloadable pdf files; teachers may pick and choose among the fourteen Encounters, selecting those that seem most appropriate to their classrooms, grade level, and goals. There is also a Resource Packet of visual materials that will aid teachers in the implementation of the encounters. Understanding that teachers work in many different situations and face a variety of challenges, The Dinner Party Curriculum Project Team has attempted to provide a range of possibilities for the integration of The Dinner Party into K-12 classrooms.

I often describe my hopes for this curriculum by stating that I see a classroom engaged in, for example, a study of the artists represented in The Dinner Party. A young student discovers Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun, the 18th-century French court painter who produced more art than any woman artist prior to her time. The student learns that Vigee-Lebrun’s achievements cannot be evaluated by art historians even now, over two centuries later, because her work has never even been catalogued. This young pupil decides that she will dedicate her life to the task, thus ensuring a role for herself in the arts, a career, and a contribution to history. Although this is only an example, it is one that would demonstrate a successful application of the enormous potential of The Dinner Party Curriculum.

I encourage those teachers who avail themselves of the downloadable materials to purchase the Resource Packet. It is a very stimulating classroom resource that will assist teachers and students in building an understanding of what was involved in The Dinner Party‘s creation.

My sincere gratitude goes to our stellar curriculum team, which was spearheaded by renowned curriculum writer, Dr. Marilyn Stewart, and includes Dr. Peg Speirs and Dr. Carrie Nordlund, all members of the Kutztown University of Pennsylvania Art Education faculty. They have been ably assisted by graduate student, Dolores Eaton. In addition, Through the Flower board member and art educator, Dr. Constance Bumgarner Gee of Vanderbilt University, has served as committee chair and the liaison between Through the Flower’s board and the Curriculum Project Team, to whom Through the Flower and I are deeply indebted.

Judy Chicago